Sometimes a word strikes our fancy, delighting us like a rainbow after a storm or refreshing us like a splash of cold water. Maybe a word is used in a novel way. Or it sparks a connection, triggers our imagination or gives us a new take on an old refrain. So we stop, and we ponder. At least I do.

Sometimes a word strikes our fancy, delighting us like a rainbow after a storm or refreshing us like a splash of cold water. Maybe a word is used in a novel way. Or it sparks a connection, triggers our imagination or gives us a new take on an old refrain. So we stop, and we ponder. At least I do.

This past week, I had such an encounter with the word “peculiar.” I was working on some FAQs about coronavirus for an insurance client. One of the questions was whether COVID-19 would be covered by workers’ compensation.

OK, sounds boring, I admit. But I learned that in order for a disease to qualify for workers’ comp, it must “arise out of or be caused by conditions peculiar to the work.” A good example is black-lung disease, which is peculiar to the work of coal miners. It’s not a disease you’ll find in any other occupation.

Being a bit of a word nerd, I was intrigued that “peculiar” had become a term of art in the insurance industry. According to Google’s Ngram Viewer, the use of peculiar reached its highpoint in 1834 and has been on a downhill slide ever since. And while insurers have continued to use the word in its original sense, today we are more apt to use peculiar to mean “odd,” “strange” or “unusual.”

The Online Etymology Dictionary dates peculiar to the 15th century, originally meaning “belonging exclusively to one person,” from the Old French peculiaire (“special, particular”) and the Latin peculiaris (“of one’s own)” Peculium is Latin for “private property,” literally “property in cattle” (in ancient times the most important form of property).

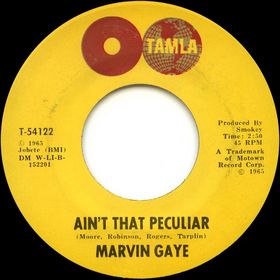

But by the 17th century, peculiar had taken on its second and more current meaning of “unusual,” “markedly different” or “out of the ordinary.” Anyone listening to Marvin Gaye’s hit, “Ain’t that Peculiar,” in 1965 probably thought Marvin was singing about how strange it was to be in love with a woman who “hurt [him] more and more.”

Ain’t that peculiar?

A peculiar-arity

Ain’t that peculiar, baby?

Peculiar as can be

But maybe, just maybe, the songwriter, Smoky Robinson, knew the etymology of peculiar. Couldn’t he have been referring to the particularity of the narrator’s experience? For anyone who’s been in (or out) of love, the emotion is surely quite personal. It’s the narrator’s pain, and no one else’s. Love may be universal, but it belongs exclusively to the person who feels it.

So my mind wondered here and there, Peculiar as can be. I began to speculate on the peculiarity of writing and wondered if any writer had ever successfully filed a workers’ comp claim for our peculiar condition, writer’s block.

As it happens, the Literary Hub has collected the thoughts of 25 well-known writers on this very subject. Well, not workers’ comp, but writer’s block. The consensus, I found, is that writer’s block is all in your head. So get over it. Consider this response from Mark Helprin, from an interview in The Paris Review:

Assuming that you are a professional and that you know how to write, why would you be unable to do so? If an electrician said, I have electrician’s block. I just can’t bend conduit. I can’t! I can’t! I can’t run wires! Help me, please! he would be committed. One thing would be certain, and that is that his paralysis in the face of his work would have only to do with him, and not with his craft. I’m of the old school, I guess, and I would call writer’s block laziness, lack of imagination, inflated expectations…

I doubt if any self-respecting writer has ever filed for workers’ comp for writer’s block. Besides, freelancers and independent contractors generally aren’t covered by workers’ comp (since they aren’t employees), unless they buy the coverage for themselves.

So ended my reverie of silliness. Then came a more sobering thought: We are in the middle of Holy Week, and Christians all over the world will be celebrating Easter on Sunday. I remembered that in the New Testament, followers of Christ are described by Peter as a “peculiar people” in 1 Peter 2:9 (King James Version):

But ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people; that ye should shew forth the praises of him who hath called you out of darkness into his marvellous light:

The King James Bible, published in 1611, most certainly used peculiar to mean a people belonging to God. For many years, I applied the more recent meaning to this verse, thinking the early Christians were unusual to believe in a crucified king, and certainly in grave danger for worshiping him. When Peter wrote his first letter to the early church, it was around 64 A.D., after the great fire that destroyed Rome. Nero was the emperor and a notorious persecutor of Christians. Indeed, it was during his reign that both Peter and Paul were executed.

Peculiar is used in the Old Testament a number of times as well. For example, Deuteronomy 14:2 says, “For thou art an holy people unto the Lord thy God, and the Lord hath chosen thee to be a peculiar people unto himself, above all the nations that are upon the earth.” Again, the meaning is clear: the people of Israel belong to God; they are distinctly his.

As we come to Easter and remember the passion of Christ, his death on the cross to end all death, and his resurrection, we celebrate Jesus’ peculiar triumph in a most peculiar time. In the age of coronavirus, unable to gather in worship houses, deprived of sharing the Eucharist, it is up to us to witness to rebirth and redemption in new ways. Yes, it is a peculiar time. But we have in Holy Week the model for the most peculiar moment in history. Let us not lose sight of that.

Thank you, Jay. Very appropriate and moving. You have given me something to ponder. Happy Easter to you and Debbie. Love and hugs. 😍

Thank you, Pat. Happy Easter from a distance!

You hit all the right notes with this, Jay! Thank you. I really like this post.

Roni, thanks!

Thank you for giving understanding of this